The Great War, Pigeons and Ontologies

The Great War

The Great War, often overlooked by its more famous sibling, was a pivotal historical event not only in politics and warfare, but also in fundamentals that shape those: ideologies, infrastructure, mobilization practices and the thing that makes all of this efficient - communications.

The methods used during those conflicts were not overengineered, they didn’t scale, so when a new kind of warfare started, the tactics, communication protocols, armament and commanders mindsets were not ready to adopt, heck, the French army was still using the bright Red and Blue uniform.

Let’s focus on communication side of things, and explore how they were handled. During early 1900s the radio communication was already an established practice. Despite its importance in air and ground coordination, the logistics were still tangled, armies needed cable laying equipment, often using horses for that, the stations were not mobile like nowadays, ground control centers, communication points and intercepting centers were needed for a full functioning pipeline. But what’s more important, the major hindrance was that transmission centers required large antennas that would give away the positions, telegraph infrastructure was a prime target during the war, artillery shells could cut-off telegraph lines, and one operation could isolate whole battalion. There were other issues too, such as interceptions and portability, during this the improvement of radio equipment would carry on and get better during the war, but the war couldn’t wait.

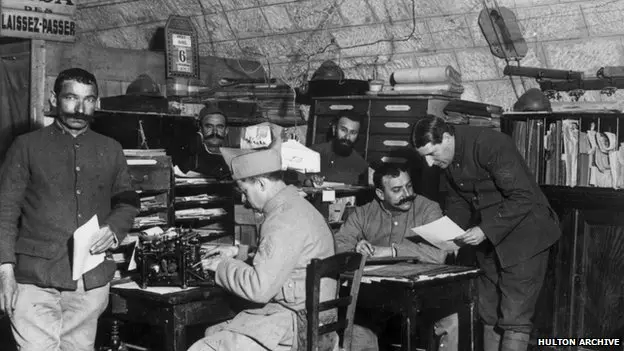

Telegraph equipment in France, 1914

Pigeons

How did armies address this, how did they make sure that the communications were less likely to be interrupted ? Contrary what people may think nowadays, humans were always smart and ingenious. We have known since at least Ancient Egypt, that pigeons have homing instincs, meaning they can find their way home even when travelling vast distances. For this exact ability, pigeons were used for carrying messages on the frontlines, often being the deciding factor between life and death, the most well-known example probably being Cher Ami.

These pigeons had small metal containers attached to their legs, where message could be inserted. The message had to be succinct, and lightweight. Important messages were often entrusted to two or more pigeons to increase the chances of it reaching the destination. Even if it did, the messages didn’t have a concrete structure, such as the message shown in the picture, which just reads: “on water attacked by 3 Huns”

For the intended reader the message was not that cryptic, and it meant that German submarines were attacking allied warship. The short message format meant that the intended recipient should have all the necessary context to act upon. And if the context wasn’t enough, it meant that valuable minutes or hours needed to be spent to clarify the message.

Ontologies

The communication failures reveal a fundamental problem that extends far beyond technology limitations. The issue wasn’t just that messages were slow or unreliable; it was that military information lacked structured meaning. Each message existed in isolation, requiring recipients to rebuild context from scratch. But imagine if you time-travelled to late 1800s, carrying with you a conceptual framework - a systematic way to organize and share knowledge that could have transformed how armies communicated entirely.

What Are Ontologies?

The framework you introduced is ontologies - systematic accounts of what exists, structured representations of knowledge within domains that show how concepts relate to each other hierarchically. These frameworks, which emerged in the late 20th century with the development of information science, could have revolutionized Great War communications through pure conceptual innovation.

Think of an ontology as a vast family tree, but instead of showing blood relations, it shows conceptual relationships. Every piece of information has a “parent” concept and potentially many “children” concepts beneath it. When you understand where something fits in this structure, you automatically understand its relationships to everything else. And most importantly, every other place uses the same exact methods to describe a single entity. Whether it’s a radio dispatcher, person reading the carrier pigeon message or a commander, they all exactly know how artillery is represented.

The Pigeon Problem

Consider what the carrier pigeon message “on water attacked by 3 Huns” actually required the recipient to understand:

- Location context (which waters, which ship)

- Force identification (“Huns” = German submarines)

- Threat assessment (attack in progress vs. completed)

- Response urgency (immediate action needed)

An ontological approach would have organized this information hierarchically. Instead of relying on ad hoc abbreviations and assumed context, military communications could have used standardized conceptual frameworks where every piece of information connected to broader knowledge structures.

Semantic Tokens

Imagine signal corps officers in muddy trenches, carefully preparing small metal cylinders not with hastily scribbled notes, but with precisely arranged semantic tokens - standardized symbols representing concepts within a shared knowledge framework. Picture a pigeon handler at German headquarters, selecting thin sheets of paper from organized compartments, each paper containing symbols that represented complex military concepts through their hierarchical relationships.

The pigeon wouldn’t carry human-readable text cramped onto tiny paper scraps. Instead, its metal container would hold dozens of these tokens, each representing vast amounts of structured information. A signals officer receiving the message would spread the tokens on a field table, instantly reconstructing not just the basic facts, but their strategic relationships and implications.

For example, instead of “on water attacked by 3 Huns,” an ontological message might contain:

Location token: [Naval-Grid-Reference-Alpha-7]

Entity token: [Friendly-Vessel-Class-Destroyer]

Threat token: [Enemy-Submarine-Unit-Multiple]

Action token: [Engagement-Active-Ongoing]

Priority token: [Response-Required-Immediate]

When radio technology could be used, these same conceptual structures would seamlessly transfer to the new medium. The ontological framework would remain constant across all message delivery methods, creating unprecedented communication efficiency regardless of whether information traveled by pigeon, telegraph, or wireless transmission.

The German High Command’s Information Crisis

To understand how ontological thinking could have changed the war’s outcome, let’s examine the German offensive toward Paris in August-September 1914. At Supreme Headquarters (OHL), General Helmut von Moltke faced an impossible information management problem. With no army group headquarters between him and seven field armies, all coordination flowed through a single overloaded channel. Orders “could take hours or days to reach units or never arrive,” while armies operated “with vague knowledge of French circumstances, other commanders’ intentions, and locations of other German units.” The critical moment came during the Hentsch Mission of September 8-9, 1914. Lieutenant Colonel Richard Hentsch received verbal instructions with “full power of authority” to coordinate army withdrawals. When a 30-mile gap opened between the German First and Second Armies, communication delays prevented coordinated response.

Now, imagine if the German High Command had possessed an ontologically-structured intelligence system. Instead of fragmented, contextless reports, OHL would have received systematically organized information that automatically revealed relationships and patterns.

WESTERN-FRONT-STATUS

├── German-Forces

│ ├── First-Army: [Position-Coordinates] [Strength-Percentage] [Supply-Status]

│ ├── Second-Army: [Position-Coordinates] [Strength-Percentage] [Supply-Status]

│ └── Gap-Analysis: [Distance-30-Miles] [Vulnerability-Critical] [Time-Window-Closing]

├── Allied-Forces

│ ├── French-Fifth-Army: [Strength-Depleted] [Morale-Fragile] [Retreat-Continuing]

│ ├── French-Sixth-Army: [Position-Paris-Defense] [Reinforcement-Status]

│ └── British-Expeditionary-Force: [Position-Gap-Vicinity] [Strength-Limited]

└── Opportunities

├── Gap-Exploitation: [Window-48-Hours] [Success-Probability-High]

├── Paris-Approach: [Defenses-Minimal] [Political-Impact-Decisive]

└── Enemy-Coordination: [Communication-Disrupted] [Command-Fragmenting]

Instead of the historical outcome during the Battle of Marn, where Hentsch ordered the Second Army to retreat at 9:02 AM on September 9 without consulting Moltke or the First Army commander, an ontologically-informed command structure would have enabled different decisions:

Hour 1: Ontological analysis identifies gap formation, calculates enemy response time, projects window of opportunity

Hour 2: Structured communication protocols instantly inform all army commanders of coordinated exploitation plan

Hour 3: Real-time updates track gap expansion, enemy reinforcement status, logistics requirements

Hour 4: Centralized command adjusts strategy based on ontologically-structured battlefield intelligence

The key difference: instead of Hentsch making isolated decisions with incomplete information during a five-hour journey between headquarters, centralized command would have possessed comprehensive situational awareness through structured intelligence flows.

The Tank

The German Army’s struggle to understand and counter Allied tanks provides a perfect example of how ontological thinking could have transformed military adaptation. When tanks first appeared at Flers-Courcelette in September 1916, German reports were so vague that “all they knew about them came from vague intelligence reports and generally inaccurate sketches.”

From a German perspective, imagine receiving ontologically-structured intelligence about this new weapon. Instead of confused battlefield reports about mysterious “moving fortresses,” an ontological approach would immediately place tanks within existing conceptual hierarchies:

TANK

├── Physical-Properties

│ ├── Material: [Metal-Steel-Armored]

│ ├── Mobility: [Self-Propelled-Tracked]

│ └── Dimensions: [Large-Ground-Vehicle]

├── Offensive-Capabilities

│ ├── Primary-Weapon: [Artillery-Gun-Mounted]

│ ├── Secondary-Weapon: [Machine-Gun-Multiple]

│ └── Tactical-Role: [Infantry-Support-Mobile]

├── Vulnerabilities

│ ├── Mechanical: [Engine-Vulnerable-Heat]

│ ├── Mobility: [Trench-Crossing-Limited]

│ └── Vision: [Observation-Ports-Limited]

└── Production-Chain

├── Factories: [Steel-Mills-Required]

├── Components: [Engine-Manufacturers]

└── Assembly: [Shipyard-Facilities-Adapted]

The production ontology would have immediately revealed systematic vulnerabilities that German strategic operations could exploit. This information would have instantly propagated across all German units through shared ontological frameworks, enabling coordinated anti-tank tactics rather than the historical pattern of isolated, ineffective responses.

Not only that, but ontological framework reveals how understanding enemy production chains could shift warfare from battlefield encounters to industrial disruption. The tank ontology shows clear hierarchical relationships:

TANK-PRODUCTION

├── Raw-Materials

│ ├── Steel-Production

│ │ ├── Iron-Ore-Sources

│ │ ├── Coal-Supply-Lines

│ │ └── Blast-Furnace-Locations

│ └── Specialized-Alloys

├── Manufacturing

│ ├── Heavy-Industry-Facilities

│ ├── Precision-Machinery-Requirements

│ └── Skilled-Labor-Concentration

└── Assembly-Integration

├── Engine-Production-Centers

├── Weapons-Manufacturing

└── Final-Assembly-Points

German strategic bombing, submarine warfare, and sabotage operations could have systematically targeted these ontologically-identified bottlenecks. Instead of random industrial targets, operations could focus on [Steel-Production] chokepoints, [Skilled-Labor-Concentration] areas, and [Assembly-Integration] facilities.

Perhaps most importantly, ontological communication would have created network effects where each piece of information strengthened the overall knowledge system. Unlike isolated messages that required complete context rebuilding, ontologically-structured intelligence would automatically integrate with existing knowledge.

When German forces captured Tank 799 at Arras in April 1917, ontological analysis could have immediately updated the entire framework.

- Updated [Physical-Properties] attributes

- Refined [Vulnerabilities] based on actual inspection

- Enhanced [Production-Chain] understanding from component analysis

Of course, there is a catch here. As the captured tank was a unarmoured trainign variant, which led Germans to underestimate the tanks. Same would happen if Germans used and updated the ontologies, and wrong [Physical-Properties] would make their way into the communiaction chain. No method is fully human-proof.

Cognitive Architecture

The real revolution wouldn’t have been technological but cognitive. Ontologies represent architecture for thinking - systematic ways of organizing information that enhance human decision-making rather than replacing it. German commanders wouldn’t need to memorize complex classification systems; they would think through problems using shared conceptual frameworks that revealed relationships and possibilities.

This cognitive architecture would have been especially powerful for the rapid adaptation required in modern warfare. When new weapons, tactics, or situations emerged, ontological thinking would immediately place them within existing knowledge structures, accelerating understanding and response.

The Great War’s communication failures ultimately stemmed from information chaos - too much unstructured data creating confusion rather than clarity. Ontologies could have provided the conceptual infrastructure to transform information into actionable intelligence, enabling the kind of rapid, coordinated response that determined victory or defeat in those crucial moments when windows of opportunity opened and closed.